Cities around the world are rapidly evolving, and people need to navigate them in more efficient ways. With growing urban populations, environmental concerns, and the need for equitable access to opportunities, the traditional car-centric transportation model is no longer sufficient. Unlike single-mode travel, such as driving your car from home to work, multimodal trips involve walking to a bus stop, taking the bus downtown, jumping on a shared bike, or walking into a park. The goal is seamless movement to meet users’ needs, enhancing accessibility, efficiency, and environmental sustainability.

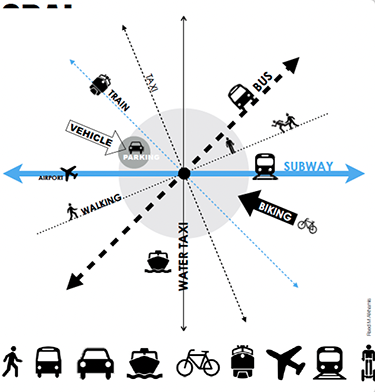

Multimodal transportation integrates all modes of travel, walking, biking, public transit, ridesharing, and more, into a unified system that’s efficient, inclusive, and sustainable. Multimodal systems are designed to connect various transit options—bikes, buses, water taxis, subways, monorails, and more- to connect transit hubs. Architects and urban designers create buildings and roads with spaces in between that enable people to switch modes safely, comfortably, and intuitively.

Activity 1 – Walking and Pedestrian Networks

Walking is the oldest and most universal form of transportation. In urban areas, pedestrian infrastructure forms the foundation of a multimodal system. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, only 3% of Americans walk to work, but cities with well-designed pedestrian networks, like Paris, have significantly more. Sidewalks (at least 6 feet wide), ramps for wheelchair users, safe spaces to pause when crossing wide roads (pedestrian refuges), and marked crosswalks make walking safer and more appealing. Streetscapes that include trees, planted beds, benches, water fountains, and transparent ground-floor facades encourage walking by offering safety, rest opportunities, and visual interest.

Plazas, mid-block crossings, and shared streets ( where cars share space with bicyclists and both yield to pedestrians ) act as multimodal nodes, connecting different transportation types and creating vibrant public spaces. In many cities worldwide, planners have demonstrated that walkable infrastructure directly boosts local businesses and reduces traffic congestion. You can walk around your neighborhood and photograph a space designed with pedestrian movement in mind. What makes it effective or not?

Activity 2 – Biking and Micro-Mobility

Studies show that nearly 60% of urban trips in the U.S. are under five miles, a distance ideal for cycling. Yet in many cities, a lack of safe infrastructure deters potential riders. Designers and planners play a critical role in complete street design with protected bike lanes (at least 5 feet wide) and secure parking. separated lanes, bike signals, and green-painted conflict zones at intersections improve safety and clarity. Architects can support bike use by including indoor storage, charging stations for e-bikes, and locker rooms with showers. New York City requires new commercial buildings to include bike parking. Landscape architects enhance user comfort by planting trees and raised beds between bike lanes and traffic, reducing urban heat and improving air quality. Check out Green Streets for more ideas to improve pedestrian safety and connectivity. Bicycles and micro-mobility tools like e-scooters and e-bikes offer fast, flexible, and affordable options for short-distance urban travel. Draw a cross-section of a street that safely supports bike traffic. Include at least one design feature that protects bikers from cars.

Activity 3 – Public Transit: Buses and Light Rail

Buses and light rail systems are the current backbone of multimodal transport. In 2022, Americans took over 4.6 billion trips on buses, proving their enduring role. However, their effectiveness depends heavily on transit-oriented design and urban planning. Well-designed stations include weather protection, digital signage, and barrier-free entry. Many cities like Minneapolis use heat lamps in bus stops to improve winter usability. Dedicated bus lanes, especially those with signal priority at intersections, reduce travel time and improve reliability. Urban designers can cluster housing, offices, and amenities around transit stops, a practice known as Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), which reduces car dependence. For example, Denver’s Union Station district blends light rail with mixed-use architecture to support dense, walkable living.

Think of one bus or light rail station you’ve used. What features made the experience pleasant or challenging?

Activity 4 – Subways and Commuter Rail

Subways and commuter rail offer high-capacity and long-distance mobility, essential in dense metro areas like New York or London. Subway systems can move over 30,000 people per hour in each direction, making them vital for reducing road congestion. Architects and urban designers must address both form and function. Station entrances should be visible, safe, and accessible. Platforms must include real-time displays, tactile paving, and lighting that ensures comfort and safety. The surroundings of stations matter, too. Boston’s MBTA is actively redeveloping parcels near its stops with housing, retail, and green space, transforming them into community hubs. In Tokyo, stations are surrounded by department stores, libraries, hotel rooms, and plazas, enhancing access and activity.

Draw or take a photo of a train or subway station entrance in your city that is well integrated into the urban fabric. What design features stand out?

Activity 5 – Cars and Rideshares

While multi-modalism aims to reduce car dependence, cars and rideshare services still play a role, especially for late-night trips, people with mobility challenges, or those in transit deserts. Urban designers address this by building mobility hubs where users can switch between buses, bikes, rideshares, and private vehicles. Designing flexible curb space is crucial, allowing areas to shift between parking, pickup zones, and outdoor dining depending on the time of day. Adaptive reuse is another opportunity. In Los Angeles, obsolete parking structures are converted into co-working spaces or vertical farms, freeing up valuable land in car-heavy districts.

Could you photograph a pick-up/drop-off zone or parking area near you? How could it be redesigned to support more than just car use?

Activity 6 – Integrated Mobility Through Technology

While multi-modalism aims to reduce car dependence, cars and rideshare services still play a role, especially for late-night trips, people with mobility challenges, or those in transit deserts. Urban designers address this by building mobility hubs where users can switch between buses, bikes, rideshares, and private vehicles. Designing flexible curb space is crucial, allowing areas to shift between parking, pickup zones, and outdoor dining depending on the time of day. Adaptive reuse is another opportunity. In Los Angeles, obsolete parking structures are converted into co-working spaces or vertical farms, freeing up valuable land in car-heavy districts.

Could you photograph a pick-up/drop-off zone or parking area near you? How could it be redesigned to support more than just car use?

Activity 7 – Designing Cities for Multimodal Use

To make multimodal systems work, the entire city must be designed with compact, mixed-use neighborhoods in mind. In cities like Seattle or Copenhagen, planners use zoning incentives to place housing, shops, and services near transit stops. Architectural elements like covered arcades, stoops, and recessed entries enrich the pedestrian experience and help link spaces. Public seating, lighting, and shade structures help create comfort along walking or waiting routes. Designing for modal change means planning safe, legible transitions, such as bike ramps into transit stations or walkways that align with train exits. Inclusive design ensures that everyone, especially seniors and people with disabilities, can use the system comfortably.

Sketch or photograph a space that helps people shift between transport modes. Label the features that support this transition.

Activity 8 – Equity, Affordability, and Access

Multimodal systems must serve everyone, not just the wealthy or healthy. Almost half of all Americans do not have access to public transit due to low-income neighborhoods being the most underserved. Multimodal systems connect dense areas in cities. Urban designers can support equity audits to ensure infrastructure investments match community needs. Community engagement is key. In Atlanta’s BeltLine project, planners held over 100 meetings with residents to shape the trail and transit corridor. Local voices, not just experts, guided the final design.

Name a place where transportation feels inclusive or exclusive. What physical or design choices contribute to that feeling?

Review

- Multimodal transportation focuses on using only public buses and trains to reduce urban traffic and environmental impact

- Shared streets, mid-block crossings, and plazas are examples of multimodal nodes that enhance pedestrian connectivity and urban vibrancy.

- Most urban trips in the U.S. are longer than 10 miles, making cycling impractical as a primary transportation option.

- Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) places housing, offices, and amenities close to transit stations.

- High-capacity rail systems like subways can move tens of thousands of people per hour and are essential for reducing urban congestion.

- Flexible curb design helps cities adapt curb space usage throughout the day. for example, shifting from parking to outdoor dining.

- Mobility apps and digital systems make it harder for users to plan multimodal trips by increasing complexity.

- Cities that support multimodal use often include mixed-use neighborhoods.